TxM 102 Taxonomy Manual Part 3: How to do it, Case Studies and White Papers and other References Created by James on 8/22/2014 4:02:38 AM Discussion of how to do it, real world complexity, challenges and opportunities, preparatory steps, design and development, coding conventions and standards, a series of case studies in which dramatic benefits accrued through use of Precision Configuration and other references

Section 7 -- How to do it

Section 7.1

The challenge

The challenge for most organizations can be summarized as follows:

1. It is abstract

2. Takes longer than you would expect

3. Costs more than you would expect

4. Requires a senior and very experienced facilitator

5. Requires significant executive and senior management time

6. If you get it wrong your organization will suffer and pay the price on an on-going basis for as long as the bad design remains in place

7. Requires maintenance by a relatively senior, well trained, well-disciplined person

8. Once it is right it is obviously right – getting there is the challenge

9. Motivating the investment is therefore frequently a challenge

Section 7.2

The opportunity

The opportunity for most organizations can be summarized as follows:

1. Make a huge positive difference to the quality and quantity of management information

2. Very considerable strategic gain through better decisions informed by better information

3. Greatly improved ease of use of all affected systems

4. Significant operational efficiencies – same staff able to do more and / or head count reduction through natural attrition

5. Grow faster and more reliably – quickly and easily conduct due diligence against own benchmarks, quickly integrate acquisitions into existing reporting schemes

6. Other operational efficiencies such as reduction in Audit time and cost.

7. This is the single most value adding investment most organizations can make relating to their business information systems (ERP, DW, BI, etc) IF it is correctly executed – JAR&A will guide you in doing this

Section 7.3

The essence of the solution

What is the essence of the JAR&A SEPT solution?

1. Strategic Engineered Precision Taxonomies (SEPT) and Precision Configuration

2. Strategic -- extremely logical content from a strategic, essence of the business, practical, common sense perspective

3. Engineered – rigorous, robust, reliable, sustainable, well designed

4. Precision – accurately models the business, easy to understand and apply, precise language, etc

5. Taxonomies – hierarchical semantic structures that accurately model the real world complexity of the business

6. Precision configuration – uses the logic of the taxonomies to develop robust rules for configuration and enables auto population of many configuration fields

7. Configure the system – be it ERP, Data Warehouse, or other repository of business data so that the system APPEARS to have intelligent understanding of the organization (through the content) and is therefore extremely intuitive and easy to use by staff with knowledge of the business from junior clerks to the CEO and shareholders

Section 7.4

Complexity

In considering complexity keep in mind the following:

1. Real business is extremely complex

2. What, why, when, how, etc

3. Simple to use systems accurately model REAL complexity

4. Internally "simple" systems that do NOT accurately reflect real complexity are DIFFICULT to use

5. Internally "complex" systems that reflect reality are EASY to use

6. Optimise system complexity versus ease of use - be real

7. KISS ("keep it simple stupid" thinking can lead to serious errors

Section 7.5

Preparatory steps for a SEPT project

The following steps should be following in commencing a SEPT project:

1. Executive interviews

1 on 1 one hour executive strategic interviews with each of the executive team and senior managers.

Questions include:

- "what is the essence of the business and how does it thrive?"(strategy)

- "critical concerns with regard to present systems"

- "critical success factors for a new solution" (not necessarily a new system)

Take detailed notes and listen attentively. Active listen by asking questions directed at gaining understanding and further insight.

2. Walkthrough the business

Including site visit/s, factory visit, warehouse visit, etc. Get a feel for the business of the business. Guided by CEO, executive or senior manager – see the business through their eyes. Followed by interviews with managers and staff coupled to walkthrough of the systems.

3. Walkthrough current systems

Evaluate the systems in the context of all the information gathered to that point. Hold up against the factors causing failure and critical factors for success. Look particularly at the configuration, Chart of Accounts, Materials / Item / Product Master, etc – do they come close to SEPT standards, where are they on the scale of 0 to 10 – refer article on this topic.

4. Walkthrough of new system

If a new system is to be installed, either an upgrade or re-implementation or a completely new system have a walkthrough of this system – main points of interest on a module by module basis.

5. Formal report summarizing findings

Write a critical factor based report with bullet points on seven plus or minus two critical findings and key recommendations. Be willing to challenge invalid thinking and to identify if the present system can be remediated. A SEPT Data Warehouse implementation is frequently the most appropriate solution.

6. Presentation to EXCO of findings and recommendations

Present the findings to the Executive Committee.

7. Plan

8. Project approval

9. Engage with executives and develop high level taxonomies

Engage with the executive to develop the high level taxonomy frameworks and then with the rest of the business to flesh-out the taxonomies. Train facilitators as appropriate.

Section 7.6

Strategic Engineered Precision Taxonomies and Configuration

Getting from where you are to where you want to be

So, having read this far you are beginning to think that a SEPT configuration is for you.

How do you get there?

Following are some important milestones you should plan for:

1. Recognize and cost the problem

Before you can go ahead with a SEPT project you need to recognize that your current situation IS in fact a consequence of imprecise and weak configuration.

It is vital that you attach a currency value to the scale of the problem you are experiencing.

Estimate the efficiency and effectiveness losses and direct costs that you are incurring at both an operational and a strategic level, the lost opportunity costs, etc. Chances are these are huge.

It is vital that you do this first otherwise the time and currency cost of the SEPT project will put you off.

If you are brutally frank about what your current sub-optimal situation is costing you you will find the SEPT project HIGHLY COST EFFECTIVE but if you skirt the issues you will jib at paying what it takes to do the job properly.

2. Appoint an executive level expert on SEPT

Before you go any further you need to find an executive level expert in the field of Strategic Engineered Precision Taxonomies and Configuration – someone who can talk authoritatively at the executive level and who can facilitate authoritatively at that level.

You do not need a lot of this persons time but you do need quality time.

Any corner cutting at this point is highly inadvisable, if you lack strategic insight in the high level design of your taxonomies you will lack that insight throughout the entire solution.

James Robertson is available to assist with this component.

This person may be supported by other staff or you may decide to have him or her train up your staff to do the "leg-work".

3. Appoint an executive level implementation advisor

This may be the same person as the SEPT expert but it also needs to be someone with lots of experience, someone with "grey hair" who can advise fearlessly at the executive level and understands the need for discipline and who can ensure that the project is run effectively.

James Robertson is available to assist with this component.

4. Information audit

Undertake a comprehensive information audit of all your systems to establish all the drop down lists, validation lists, master lists, class lists, etc that occur throughout your organization.

Organize this on a logical entity basis and document exactly what the vendors of the software say the field is supposed to do, what software functionality is linked to the list and what content is in the list at present. The present content is useful as a "brainstorm" list but does not necessarily contain the correct information.

Based on this audit map out the priorities in terms of developing taxonomies on a 20:80 basis – what is the 20% of the SEPT effort that will deliver 80% of the SEPT benefits?

5. Plan the project

Plan the project taking account of the JAR&A Critical Factors for IT Implementation Success and running the project so as to prevent the Critical Factors Causing IT Implementation Failure from kicking in.

It is vital to plan for taxonomies and configuration to lead and process to follow.

6. Purchase taxonomy development, deployment and maintenance software

Precision taxonomies can be developed to a point in spreadsheets if you have someone who really understands the principles and conventions well but in terms of generating and managing precision taxonomies software is vital.

James Robertson and Associates are in the process of developing a suite of taxonomy software which will soon be available for purchase to assist in the entire spectrum of these facilities. Our goal is to give you access to knowledge based software that taps into as much of the knowledge and experience in the head of James Robertson and possible.

7. Develop the high level structure of your new taxonomies

Assisted by the executive level expert mentioned above, develop the high level structure of your taxonomies. This must take place through engagement with your executive team.

Refer to the section on "The power of an executive with a blank sheet of paper" — it is VITAL that you start with a clean sheet and do not attempt to panel beat an existing list – you can always map your old list to your new list subsequently but there is absolutely no point in trying to beat your beaten up information jalopy into a new shape J

8. Develop detailed taxonomies and configuration

Once the high level structure of the taxonomies has been developed more junior personnel, either from your own organization or the service provider can facilitate the development of the full detail of the taxonomies assisted by the SEPT expert referred to above.

9. Deploy in a new instance of your Data Warehouse and in time your ERP

Once the taxonomies have been developed deploy them FIRST in the ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) layer of your Data Warehouse in a NEW instance of your Data Warehouse technology with a NEW implementation of your BI tool, or buy a DW and BI tool and start from scratch.

The mapping and transform exercise onto your ERP will be tedious, frustrating and slower than you would like and the debugging will be painful, however, once it is done, provided you are disciplined about maintaining the mappings you will have done the 20% of the work that will unlock 80% of the value of precision taxonomies in your business.

In this process you will have to add some detail to the lists in your ERP and may have to repopulate some lists immediately.

This is where you will unlock much of the value – develop a full suite of simple and advanced management reports, models, analytical tools, etc and start to get insight into the operation of your business.

Later you MAY decide to start trickling the new taxonomies down into your ERP in a very controlled manner recognizing that every change you make WILL break things in the ERP configuration. Provided this is done carefully and systematically these risks can be contained and eventually you will achieve the 20% of the re-implementation of your ERP that will unlock 80% of the benefits of SEPT in the ERP.

In my experience, unless your ERP is terribly badly implemented this approach will give you a more than adequate outcome -- the cost of a full-blown laboratory based implementation is just too great for nearly all organizations.

SEPT offers huge benefits which will far outweigh the time and cost of executing the SEPT project provided you are brutally frank about what your current configuration is really costing you!

Section 7.7

Design and development stages

The following are the stages in design and deployment of SEPT taxonomies and Precision Configuration:

1. Fundamental strategic understanding of business drivers

a. Primary focus for measurement

2. Fundamental definition of business, product, etc entities and relationships

a. Define primary components to be measured

b. Business model, market model, etc

3. List all possible information

a. Research and brainstorm

b. Past and present information

c. Likely future information

4. Structure the data

a. Hierarchical first principles classification of all possible information

b. based on strategic analysis and entity analysis

c. Everyone understands

d. Fundamentally intuitively sound

e. MultiStage© picklists in software if possible

5. Semantic analysis

a. Fit the text to the display field

b. Words are all the operator has to decide what to post to

c. Standard suffixes

d. Standardise abbreviations

e. Hierarchy builds a sentence

f. No ambiguity, no non-conformities

6. Code the structured data

7. Apply business rules

a. Limit display of lists to the components that apply to a particular operator or location

b. Corresponding rules in software

c. Classification of fields on lists

Section 7.8

Categories of lists

There are a variety of types of list which have distinct attributes in terms of the design of the taxonomies that go with the lists:

1. Random name based lists

The simplest type of list is a randomly generated alphabetically sorted list of customers, suppliers or other comparable data.

Items are added to the list as business proceeds and there is no logic or control over what gets added to the list.

For such lists it is not possible to develop a taxonomy although it is possible to adopt coding conventions such as first three characters of the supplier name followed by a three digit sequence number for repeat occurrences of that name.

The same approach applies to personnel codes for software access control, etc.

Examples would include STA001 for Standard Bank or RobertJA001 for James A Robertson.

The value of having a standard code format is that references, etc are more consistent and the list appearance is neater and it is easier to manipulate the list electronically.

The number of characters and number of digits would be determined from consideration of the size of the organization and foreseeable growth over say the next ten years. Ease of remembering the code and ease of interpreting the code is also a consideration.

The classification of suppliers, customers, etc will fall under the simple or intermediate validation list category of lists.

2. Project and other time sequential lists

Project lists have the distinct characteristic that the list grows in time with no other logic.

In some cases one might use some intelligence in a prefix such as RJ00175 where the RJ represents projects run by project leader Robertson James (RJ) and 00175 is a sequence number which indicates that this is the 175th project under the control of that project leader.

The number of digits is determined from consideration of the maximum number of projects that can reasonably be foreseen for one project leader in the next ten years or similar.

This code provides a short-hand referencing method that allows transactions such as time sheet entries, purchase orders, etc to be directly linked to the project.

In cases like this I recommend the use of a check digit such that the above example would take the form RJ00175c where "c" represents a check digit that might be the rightmost digit of the sum 1x5 + 2x7 + 3x1 + 4x0 + 4x0 where each digit of the code is multiplied by some factor and the composite code gives rise to a check digit which is a direct function of the numeric elements of the code. In the above example the sum would be 5 + 14 + 3 + 0 + 0 = 22 so the check digit would be 2 (rightmost digit of 22) and the full project number would be RJ001752.

There are more sophisticated algorithms for check digit calculation and check digits can be computed on the alpha component as well if required.

The goal of the check digit is to ensure that if a typing error is made and two digits are transposed during data capture the resulting erroneous number is unlikely to be a valid code. This is important in any situation where high speed, high volume data capture is required and greatly improves data accuracy.

Complex check digit algorithms are used in Credit Card and other bank account number generation.

Note that bank account number generation is a specialized field which is outside the scope of this handbook.

Check digits could also be used with Customer codes and Supplier codes as discussed in the previous section.

Check digits can also be used for sequential detail in Material Master type data at the finer levels of the code where time-sequential data may be recorded.

The classification of projects will be a simple or intermediate validation list.

3. Simple validation lists

Simple validation lists are lists in any location in software where simple classifications occur. Perhaps the simplest example would be Gender – e.g. Male, Female, Unknown for "Gender of purchaser".

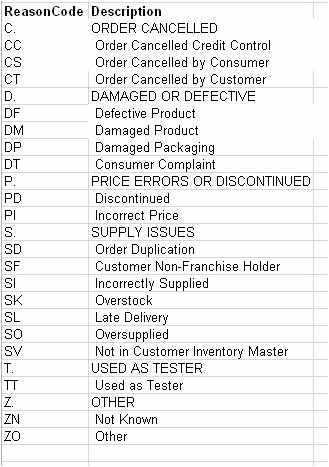

This would extend to things like Credit Note Reason Codes, basic classifications of products, etc.

There are innumerable examples of simple validation lists in well-designed software.

These lists may drive software intelligence.

I would classify a simple list as having one or two levels of hierarchy and, by extension, not more than about 50 entries.

In most cases with strategic executive input the content of such lists is finite and can be circumscribed at a level that the list can be built in such a way that it will not change much over time.

4. Intermediate complexity validation lists

Intermediate complexity validation lists are simply more complex lists than the simple lists discussed above.

Examples would include Locations and Functions in the Cubic Business Model and would have between three and five levels of hierarchy.

Intermediate lists can be encountered anywhere in software where reasonably complex data is classified.

As with the intermediate lists the scope can be reasonably clearly defined with strategic executive input taking a medium to long term view of where the business is going.

5. Charts of Accounts

The Chart of Accounts is typically a very specific form of complex list which will tend to have between five and ten levels of hierarchy and between 1,000 and 10,000 entries.

A Chart of Accounts is a distinct taxonomy because its design is based on accounting principles and conventions and for any business its scope is distinct and finite – it is therefore generally possible to build a Chart of Accounts that will last for many years with minor changes PROVIDED the General Ledger is used effectively and the business does not attempt to include excessive evolving detail in the Chart of Accounts.

Notwithstanding the above comment, a well-designed Chart of Accounts taxonomy will accommodate considerable change and growth over many years.

A Chart of Accounts taxonomy will typically be numeric only with occasional exceptions where business considerations indicate that Alpha is required to accommodate specific logic or more than 10 items occur at any level in the hierarchy (generally NOT recommended).

6. Product / Material / Item Master lists / classifications

In most organizations the content of the Product Master, Material Master, Item Master or equivalent list is diverse and complex and complex hierarchies and code schemes result.

These are the most complex lists.

In some cases the Product or Material list will be an open ended random list coded on the basis of EAN Barcode or other random sequence number allocated by suppliers, in this case the logic must be contained in the Product Classification, Material Group or other comparable list.

Product / Material and Item Master lists can include elements of all the other categories of logic and coding listed above.

7. Cubic Business Model

The cubic business model is a multi-dimensional assembly of taxonomies (lists) to model the business and results in a three or more segment compound code scheme comprising business divisions (business units), physical locations, functions and specific accounts picked from the Master Chart of Accounts.

The first three dimensions of this code scheme also apply to the categorization of personnel, assets and other physical elements of the business.

8. Project plan work breakdown structures

Project plans have a very specific logic insofar as they map out the logical progression of a project from start to finish.

Most project plans are NOT designed from the perspective of the management of the project towards an outcome but are designed from consideration of estimating the project in the first place. This is NOT the right approach.

A plan that can be used for management requires a consistently fine level of granularity at the work execution level with work packages that might be classified as "parts, tasks and activities" in reusable modules that take account of the human aspects of project execution. The lowest level activities should have an execution time-span of between one and three weeks so that for monthly progress reporting an activity is either not started, in process or completed and is not in process for more than one month.

This is the only way to really evaluate the progress of a project from a management perspective.

This is over-and-above the application of the principles of precision taxonomies advocated in this handbook.

9. Filing and document classification

Filing and document classification as a standard across an entire enterprise is vital to the longevity of information.

The filing and document classification scheme should apply to the full spectrum of documents generated in an enterprise and should be applied to storage on local and network disk drives, manual filing, etc.

Again there are specific principles to be applied to this genre of classification scheme over and above the principles applied in this handbook.

10. Other lists

To the best of my knowledge the above categories apply to the full spectrum of information that it is required to catalogue and classify information in organizations. Should you identify categories of information that seem to lie outside the above I suggest you look carefully at the possibility that the principles catered for in the above nine categories will somewhere cater for your data.

If you still cannot find a category that applies you are welcome to contact me.

The above categories cater for every type of list and provide a basis for formulating an approach to classifying and coding information.

Section 7.9

Important questions about any data

In considering developing taxonomies relating to any data keep in mind the following:

1. What is the fundamental information in this table?

2. What category of information and how do we code effectively?

3. Who will use it?

4. How will they create value with it?

5. Could we need this sometime in the future

6. Is the information readily available or what will we do to obtain it?

7. Who will be inconvenienced by obtaining this information?

Section 7.10

Steps in developing a hierarchy

Strategic engineered precision taxonomies (SEPT) require the development of highly structured taxonomic hierarchies, the steps in developing such hierarchies are as follows:

1. Accurate identification of the list

Make sure that you clearly understand the purpose and the ambit of the list from careful consideration of the exact name of the list and also understanding of how the software references and uses the list elsewhere (if applicable).

I frequently encounter lists which contain content that bears no relation to the name of the list or the purpose of the list in the software. Then people blame the software for not working correctly and build workarounds that get more and more complex and remove the operation of the software further and further from its original design.

It is vital to understand that it is extremely bad practice to use a list for something other than its intended purpose.

If you identify an information need and there is not a suitable list then it is preferable to add a user defined field rather than bastardize an existing list.

2. Entity-relationship logic

Entity-relationships define the relationship between different logical entities and their corresponding data tables, thus, for example, a business has customers and customers have orders and orders have order lines. Validation and other lists and fields should be incorporated on the data tables that are appropriate to the logic of the REAL WORLD.

Failure to do this will result in all sorts of apparently aberrant behaviour by the software and all sorts of workarounds, etc. It is vital that the real world logic is accurately modelled.

If you are not familiar with the rules of entity-relationships I recommend that you find someone who is to advise you before you use a list for a purpose other than that for which it is intended. It is no good setting up well designed content in a list that is in the wrong logical location in the database and then complaining that the software does not work properly.

3. Start with a clean sheet

Start the design of the hierarchy with a clean sheet of paper / spreadsheet / worksheet, do NOT under any circumstances try and fix an existing list (unless you are cleaning up a really well designed list that has been badly managed) – you will waste large amounts of time and produce a sub-optimal outcome.

The human brain is a highly powerful, abstract, cognitive super-computer – use the existing lists as a source of brainstorm material but build the new taxonomy on a clean sheet. See the article "The Power of an executive with a clean sheet of paper".

4. Cascade

The hierarchy MUST cascade. Indent each row down the hierarchy by one character in the form of a leading blank space.

This is vital in order to ensure that the hierarchy is easy to read by personnel posting against it in the future and also to ensure that the logic of the hierarchy flows smoothly. The visual effect of the indents ensures that the hierarchy is easy to interpret.

5. Capitalize headings

In building the taxonomy capitalize the headings and in application of the hierarchy train staff NOT to post to headings EXCEPT in the case of budgets and mappings which may post to headings.

All possibilities that apply to a heading should be listed under the heading.

The use of capitals is also for ease of reading when posting and when summarizing reports.

Posting level lines should be in lower case with the first character of the description and proper nouns capitalized.

6. Identify the type of list

Refer to the different types of list and make sure that you have correctly identified the type of list (and data) that you are working with and that a hierarchy is, in fact, applicable. Note that there are distinct principles that apply to developing hierarchies for different types of data.

7. Comprehensive view

Develop a high level view of the total ambit of the information required in the hierarchy through intuitive understanding and / or getting the right person or people in the room and / or through research.

Generally this means consulting with senior business people, particularly with regard to something like a group-wide Chart of Accounts or Item Master, etc.

8. Push the envelope

Push the envelope in terms of possible future growth – consult with executives in terms of possible future growth and provide headings and gaps to accommodate foreseeable growth.

9. Develop major categories – 5 to 9 optimum

Formally or informally develop the major categories that describe the content of the hierarchy. Generally aim for between 5 and 9 headings with the optimum being 7.

If there are 5 or less items look for ways to split some of the headings into more than one category and increase the number aiming for 7.

If more than 9 look for ways to group categories to reduce the number, aiming for 7.

With large hierarchies you may need to iterate several times before you get this right.

I consistently find that where I take more time to refine to close to 7 categories the final list is tighter and makes more business sense than lists with 5 or less or 9 or more items.

10. Multiple dimensions

Sometimes you will find that you come up with more than one set of equally valid groupings.

This may indicate that the naming of the list is too broad or is ambiguous in which case you may need to split the list into two or more attribute sets and add one or more additional user defined fields to the relevant data table.

Alternatively you may duplicate the second list down the first list for every instance to create a simulated matrix list. The correct treatment for such a situation is to recognize that you have identified a matrix type of relationship and then to build the resulting matrix or cube in accordance with the principles applied to the Cubic Business Model for financial data.

The key consideration is to accurately model the real world.

11. Locations

Locations should follow a logical geographic progression that makes sense in the context of the geographic distribution of the organization – for example clockwise round the country, or the world, etc.

12. Functions

Functions should be arranged logically such that the most core functions are at the top of the list and the least core functions at the bottom. A useful test is "is this something that I could easily outsource?" — if so this is NON-core. If you cannot outsource it easily because it is a key differentiator or represents the essence of the business then it is CORE.

13. Iterate to fine granularity

Depending on the scale of the subject area iterate down the hierarchy in each segment until you reach the posting level as determined by the "screw metaphor"—that is small and unambiguously unique bins each of which contains data with one explicitly unique and mutually exclusive combination of attributes such that ALL permutations are catered for by explicit bins.

Take time to brainstorm and research ALL possible elements for any component of the hierarchy.

14. Element sequencing

Sequence the elements in any component from a strategic fundamental first principles view point such that the strategic (essential) elements are at the top of the list segment and the most operational (least strategic) are included at the end of the segment.

15. Multi-faceted hierarchies

Note that on large complex hierarchies such as the Item Master or Materials Master or for document filing schemes there may be different logic for different components of the hierarchy. These will ultimately give rise to compound, complex code schemes.

16. Languageing the hierarchy

As you build the hierarchy language each level of the hierarchy very carefully so that reading down the hierarchy tells a very detailed story – a comprehensive and unambiguous reading down to the posting line.

This must take account of the different rules that may apply to different levels of the hierarchy – for example core operating consumables for an earth moving machine may be identified explicitly, as in the case of an air filter whereas seldom purchased body parts may be classified using a sequence number in the code scheme and only added when required,

17. Exceptions -- Other

Where "Other", "Unknown" or "Not applicable" are valid options provide for them at the end of the relevant hierarchy list components and code appropriately.

Note that there ARE times when one or more of these logical elements IS valid and needs to be provided. If they are provided they should be coded appropriately and managed with appropriate exception reporting, that is a report listing all instances of "Other".

By way of example I nearly always code "Other" as "9" in a numeric code scheme or "Z" in an alpha or alpha-numeric code scheme so that it is at the end of the list element. The fundamental logic is that operators must scroll past all valid options before selecting "Other" and that accordingly "Other" will only be used under exceptional valid situations.

Basically "Other" should only be used when an operator requires training as to where to post or where some instance occurs where there genuinely is a transaction that is not catered for in the body of the code scheme. In the first instance training should be given and in the second an additional code should be added if "Other" is occurring reasonably frequently. With this philosophy "Other" is valid and should be catered for and managed.

During implementation it is recommended that reports are produced to list all instances of "Other" so that they can be managed as suggested above.

18. Calibration

Once the lists are thought to be complete, hold up the new lists against the old lists and tick off line by line to ensure that everything on the old lists is catered for on the new lists. Sometimes this can be done as part of the mapping process linking old to new codes but this checking should generally take place well before the mapping stage in order to avoid having to add codes during the mapping process. This will ensure that the mapping process will proceed quickly and smoothly.

The above is an outline of considerations and steps in the development of a hierarchy. I hope to produce more detailed material in due course.

Section 7.11

Steps in coding a hierarchy

Strategic engineered precision taxonomies (SEPT) require the development of highly structured taxonomic code schemes linked to the hierarchies. The steps in developing such code schemes are as follows:

1. Build the hierarchy keeping coding in mind

As you build the hierarchy take account of how you plan to code taking account of the different coding styles that are available to you.

2. One level at a time

Build the code one level of hierarchy at a time – follow the colour coded columns corresponding to the indents of the hierarchy and work all the way down from top to bottom adding codes at the start of each level of indent and then spacing codes out over the remaining section of the hierarchy.

3. Use one character per indent

Most frequently you will use one character / letter / number for each level of hierarchy but in some cases, primarily with complex code schemes of the Item Master / Material Master / Product Master genre you may use more than one character. In such complex hierarchies you may use different code patterns for different levels of the code hierarchy.

4. Gap code

It is vital that you gap code – at every level of the code scheme spread the code out as much as you practically can leaving larger gaps in areas where it is most probable that further detail might be added in future.

5. Follow list sequence

The code sequence MUST follow the list sequence.

If while coding you see an opportunity to improve the list sequence then change the list sequence and code accordingly.

Where you change the list sequence please notify other team members of your action in order to avoid "people" problems later.

6. Mnemonic is preferred

Mnemonic alpha coding is always preferred with the mnemonics corresponding to the hierarchy.

There are, however, distinct rules that apply in large code schemes.

7. Delimiters

Codes should be structured in segments with delimiters such as "-" (preferred), "/", "_" or "." depending on the code scheme. Multi-segment codes such as the Cubic Business Model Chart of Accounts should have segments delimited. Most software can handle "-" or "." as a delimiter and these have the advantage of being on the numeric pad, some people favour "/" which is also on the numeric pad. Once you have chosen a delimiter stick to it.

Where a code element, such as the Chart of Accounts exceeds four characters in length this should also be split into segments. The human brain interprets and remembers three character or four character blocks most readily so code segments should be kept to between three and four characters wherever possible, for example 172-9343-013.

8. General ledger coding

In the case of general ledgers there are usually accounting and business requirements that dictate the sequence of the lists and this points to numeric coding.

In addition, most accountants prefer numeric coding on the basis that it is allegedly faster and more accurate for bookkeeping staff. However, I have encountered accountants who prefer alpha-numeric – decide the coding convention before you start coding.

9. Alpha sequence code

In cases where the code scheme is very cramped you may use Alpha as a sequence code with no correlation between the letter used and the corresponding list entry.

10. Mnemonic logic

In mnemonic coding the progression of logic is as follows:

a. First letter match

b. Next matching consonant

c. Letter sequence

d. Relevant vowel

e. Number

The goal is to follow the sequence of the hierarchy with coding that is most intuitively easy to remember.

11. Strategic (essence) logic leads

Note that the strategic (essence) logic of the sort order is more important than the ease of remembering as the human mind has great capability to remember patterns.

12. Check digits

Sequence number coding should, as far as possible, always include a check digit in cases where several characters are allocated to the counter.

13. Sort order

When coding make sure that the sort order of the code always correlates with the physical position sort of the hierarchy.

The above is an outline of considerations and steps in the coding of a hierarchy. I hope to produce more detailed material in due course.

Section 7.12

Coding steps

The following steps should be followed in developing codes:

1. Exception handling

a. Not Applicable, No Information and No Code (Z00, ZNA, ZNI)

b. Always a place to post EXACTLY

2. Ease of interpretation and remembering

a. Mnemonic where possible

b. Alpha numeric where mnemonic is not possible

c. Numeric where alpha is not meaningful e.g. chart of accounts

3. Contiguous bracketing

a. NO gaps

b. Codes cover entire possible range e.g. "End of ..."

c. Codes for start and end of range

4. Consistency across lists and entities

a. Same items same structure and code everywhere e.g. assets, depreciation, insurance, repair and maintenance, etc

5. Conventions

a. Capitalization

b. Indents

c. Trailing periods

d. Delimiters

e. Abbreviations

6. Single entity per list UNLESS by conscious CHOICE -- Model full multi-dimensionality

7. Generate complete lists and audit reports

a. Duplicate standard modular blocks

b. Reports to audit postings

c. e.g. rigorous analysis of GL

Section 7.13

Critical implementation considerations

Following are some critical considerations in implementing SEPT and Precision Configuration:

1. Radical change

SEPT and Precision Configuration are a radical change compared to what your organization has today (else you would not consider the investment) – some staff will intuitively see the value and actively embrace the new way of working but many will be unsettled and some WILL resist.

2. Trash the old ways of working

A wide range of historical ways of working, protocols, policies, standards, procedures and processes will be trashed or radically changed and some staff will be offended and oppose the change.

3. Minds go blank

The mental reaction of most human beings when confronted with something new and unfamiliar is to "go blank" – for this reason there must be comprehensive communication with, and involvement of, staff during the design and implementation process. Use of a laboratory for testing and training is recommended – see the article "Defining an ERP implementation laboratory".

Staff must be facilitated through the difficult transformation and the services of a change facilitation advisor, preferably with a degree in psychology, is recommended on larger projects.

4. The Old reports

The default requirement with any new taxonomy is to produce "the same reports as we had before" – this is understandable but is NOT recommended. Remapping the new taxonomies onto the old reports can be a time consuming and painful process and is NOT recommended unless the old reports are really well designed.

It is better to design new reports from the ground up (blank sheet of paper) exploiting the design of the new taxonomies and then transform the historical data to the new mappings and run the new reports against the old data.

If it is decided that the old reports must be recreated then it is vital to understand that this is a time consuming and frustrating process which does NOT say anything negative about the new design.

Note that in producing the new design consideration should be given to standard reporting requirements although, given these were derived in an environment of badly structured data care is required in making such historical references.

The blank sheet of paper is the preferred route.

5. Blame the new

Inevitably it takes time to debug and define reports, ETL, etc and when problems are experienced it is all too easy to blame the new configuration and suggest that somehow it is fundamentally defective.

Provided the taxonomies have been developed in close consultation with management and staff and comprehensively reviewed it is extremely unlikely that there will be any significant structural defects in the code schemes – the reaction is simply a natural negative reaction to change and things which are not yet fully understood.

6. A system implementation

The implementation of new code schemes in an existing technology system, whether in an ERP, Data Warehouse, Business Intelligence environment or other system have all the characteristics of a full-blown system implementation. It can therefore be expected that all the problems and challenges associated with such an implementation will be encountered and must be managed effectively.

7. Lack of knowledge of what is possible

Most people are not familiar with advanced graphical, statistical and other analytical techniques and accordingly executive level advisory services to assist with the development of advanced reports, models, etc should continue for at least a year after commissioning of the new taxonomies.

8. Appoint an analyst

In medium to large client organizations we recommend the appointment of a senior or mid-level staff member or contractor with formal training in statistics and data analysis techniques, economics, etc and equipped with advanced analytical tools.

Section 7.14

Conventions and standards

Strategic engineered precision taxonomies (SEPT) are THE way to give executives REAL information:

1. Not about technology, about INFORMATION

2. Strategic understanding

3. Fundamental first principles

4. Long term view

5. Complex, challenging and costly BUT substantial net value

6. Perhaps the greatest "I.T." BUSINESS VALUE opportunity at present

7. Do not scrap your existing systems UNTIL you have thoroughly evaluated and costed this option - look at customisation and re-implementation

Section 8 -- Case studies and white papers

Section 8.1

V3 ERP Implementation case study -- headlines

The headlines of the V3 ERP Implementation case study are as follows:

1. ERP that James Robertson was involved in architecting and designing

2. Cubic business model based on Chart of Accounts resulting from 1,000 hour investment

3. "More management information than we know what to do with" – very happy client

4. One less bookkeeper

5. Audit complete in six weeks, previously six months

6. Balance sheet unqualified for the first time in fifteen years

7. Presentation with client – greatest recommendation

The Benefits of Management Information Systems to the Professional Practice

SAICE 15th Annual Conference on Computers in Civil Engineering

By

Dr James A Robertson PrEng & Reg M Barry, Financial Director, V3 Consulting Engineers

SYNOPSIS

The advent of commercially available practice management software for the South African Consulting Engineering Industry some years ago, introduced the possibility of introducing far reaching, tailored, management information systems into the professional practice. This paper sets out to highlight some of the experiences and particularly the benefits derived from one such installation two years after implementation. The system comprises an integrated job costing, billing, debtors and creditors system linked to a comprehensive financial management system and an executive information system offering a wide range of management reports and graphical analysis.

Benefits experienced include the reliability and timeousness of the information, financial results are typically available within ten days of month end and year end financials within the same time frame at reduced audit cost and greater precision. A wide variety of reports are available and the organization can be viewed as a "Rubics Cube" of information in which the information can be grouped and examined in a wide variety of ways allowing project, client, profit center and other views of performance according to management's needs. Full activity based financial analysis and overhead distribution is supported eliminating the approximations typically made in assessing profit distribution and recognizing marketing and management contributions.

Senior management have had their workloads on mundane analysis greatly reduced while obtaining more accurate information faster. Information is also available at different levels of the organization at different levels of detail. Enquiries from a very summarized executive view to a very detailed transaction level analysis allow effective management by exception with drill down to specific problems. The variety of analyses possible offers great scope for effective management and directed marketing in a manner which should allow the company to create and sustain competitive advantage.

INTRODUCTION

The evolution of computer technology in the late eighties gave rise to a situation at V3 Consulting Engineers in 1989 where the existing projects system was becoming obsolete and no longer able to cope with the demands of the firm. Over the period 1989/90, the management of the firm undertook a number of preliminary reviews of commercially available software and subsequently commissioned a detailed study of the firm's requirements in which the relative strengths and weaknesses of the commercially available software packages was evaluated (Robertson 1990).

It was established that neither of the major packages available were ideally suited to the needs of the firm and further analysis was undertaken to establish in greater detail the scope of modifications required. Following negotiations with the vendors, a scope and budget for the required changes was agreed and a final decision taken as to which system to purchase. The selected system was a South African developed package already in use at a number of consulting engineering firms.

A period of software enhancement by the developers was followed by testing and pilot operation, the system was commissioned and ran live in the Cape Region of V3 in October 1991. Thereafter the system was installed in the Free State and Transvaal regions, running live from March 1992.

This paper outlines some of the experiences with the implementation with particular emphasis on the benefits derived from the use of the system.

SYSTEM OVERVIEW

The system selected comprised a number of major components:

Projects System

The projects system comprises a suite of programs including projects and personnel databases, salary and rates information. A company parameters module allows configuration of the system to model the organizational structure of the practice to take account of offices, departments and associated companies as well as to define the nature of the general ledger interface. A variety of set-up options allow further customization of the operation of the software.

The projects system provides full features for the entry and processing of time and expense information with comprehensive analysis of Work in Progress (WIP). WIP is maintained on an open item basis such that once captured, all items remain in the system until they are either recovered through billing to the client or written off. Full audit trails and analysis reports are available on the WIP. The project system includes a largely automated billing system.

The projects system also provides a wide range of facilities for structuring up to 5 levels of project detail and associated analysis together with activity codes and a variety of project budgeting and reporting options.

The projects system is integrated with debtors and creditors modules to allow full management of these accounting functions with project related reporting in debtors and both project and non-project expenses posted in the creditors program.

All financial components of the projects system are integrated on a batch basis with a commercial general ledger package.

Financial System

The financial system comprises a commercial general ledger package together with integrated cash book software. This is linked on a batch basis to a commercial salary package. The financial system has recently been extended by the acquisition of an integrated assets register package and barcode reader. The financial system replaced 24 column manual cash books.

The general ledger chart of accounts accommodates a comprehensive, fundamental analysis of all income statement and balance sheet items in a manner that is linked to the business model of the organization in terms of cost and profit centres including physical branch offices and administrative, technical and support departments. A hierarchical, structured coding scheme is employed in order to facilitate allocation of expenses on an activity basis, and to allow progressively more detail in enquiries. Associated with the chart of accounts, a variety of financial reports allow summary or detail reporting for the region, office or department as required, including summary and detail income statements, balance sheet, cash flow projections and ratio analysis.

The financial system is linked directly to the projects system in a manner that is designed to support activity based costing and allocation of income and expenses in a manner that permits clear definition of ownership of information with a view to achieving a high level of internal auditing and a resultant improvement in accuracy and reduction in audit delays.

National Consolidation

In the past year, procedures have been implemented to permit all financial results to be consolidated nationally at the detail level, thus permitting the extraction of a wide variety of detailed and summary analyses. Various controls on inter-region charges have also been implemented together with procedures for accumulation and distribution of corporate overheads.

Executive Information System

Recently a graphical Executive Information System (EIS) has been developed to operate on the underlying operational projects and financial systems. This EIS has been developed using a commercial, windows based tool and provides a high level of graphical summarization of certain key values in the projects and financial systems. Development is continuing.

The EIS system has been developed with the objective of enabling senior management to see key values summarized graphically in a meaningful way that allows them to rapidly identify potential problems and drill down to the detail in any way that they may consider necessary. Particular emphasis was placed on achieving a user interface that was intuitive for senior management and did not restrict enquiries on the basis of simplifying assumptions made during construction. The EIS also provides an interactive mechanism for overhead distribution on an activity basis, whereby all income and expenditure relating to non-production business units is distributed over the production units on an agreed basis. The model has been designed with a view to providing management with the means to examine the effect of alternative allocation formulae on the profitability of individual business units without altering the underlying data which has been allocated on a fundamental basis.

The ultimate objective set for the EIS is to support a "paperless board meeting" in which all relevant information is projected onto a screen in the board room so that managers can analyze and query information interactively and pro-actively thus facilitating management by exception rather than tabling large volumes of information.

OBJECTIVES FOR THE SYSTEM

A number of short term and long term strategic objectives were set for the system at the time that the initial investigation (Robertson 1990) was undertaken. Particular emphasis was placed on specifying the objectives and requirements for the system with the objective of meeting the long term strategic requirements of the firm with a view to avoiding the need to replace the system after a few years. Objectives set included:

- Provide tools to monitor and improve productivity and profitability.

- Enable profitability to be measured on a project, department and office basis using the cubic model proposed by Robertson.

- Assist the firm to offer the highest possible levels of service to it's clients.

- Ensure that charges for work were realistic and that work was performed effectively for the client.

- Provide comprehensive budgeting facilities for projects and financials.

- Assist in the evaluation of current and future directors with respect to appointment and promotion.

- Provide concise management summaries.

- Permit a global view of the practice.

- Permit detailed enquiry on all aspects of operations and job costing.

- Require minimum management time and manpower to operate system.

- System must be affordable.

All of these objectives have been met at the current time although costs have been greater than expected and would be handled differently if the project was undertaken today. Certain specific benefits are discussed in more detail in subsequent sections.

IMPLEMENTATION EXPERIENCE

The implementation was undertaken in a phased manner, as outlined previously. Problems were experienced in terms of availability of senior personnel in-house at certain times and in terms of commissioning the system in other regions using in-house personnel. This was undertaken with a view to cost containment but ultimately gave rise to increased costs associated with correction of problems experienced.

With hindsight, more use should have made of outside assistance in the implementation in the second and third regions. In-house staff were not experienced enough and the time they spent in other regions placed pressure on their own region's operation.

Time taken to achieve understanding and commitment to the new system by managers and staff at all levels proved to be greater than anticipated and required focused and firm action by top executives before all required information was provided by project leaders and other staff and proper use was made of management reports. Experience tends to support the widely reported view that a paradigm change of this magnitude requires between three and five years to become permanent in an organization.

BENEFITS OF THE SYSTEM

The projects system has now been in operation in the Cape Region of V3 for close to two years and in the rest of the country for eighteen months while the financial system has been in use country wide for eighteen months. As stated above, the objectives set three years ago have all been met. Specific benefits are discussed in the sections that follow:

Reliability and Timeousness of Information

Information is readily available, in many cases almost instantly. For example, analysis of time sheet data and other data captured to projects is available within two working days of the end of the month.

Full analysis of project performance for the month is available immediately data capture is completed including a wide variety of budget, costing and profitability reports. Up to date sales journals are available at any stage as are debtors and creditors age analyses. The EIS projects analysis can be made available within twenty four hours of month end or updated more frequently as appropriate.

Full financial statements including summary and detailed income statements, balance sheets and cash flow projections are generally available ten days after month end and include all closing and balancing adjustments for the period in question so that there is considerable confidence in the reliability of the information. The EIS financial analysis can be made available at the same time.

Because of the wide variety of combinations and groupings in which the information can be presented and the wide variety of controls built into the system, it is possible for all information to be reported in a manner which allows recipients to accept full ownership of specific sets of data. This facilitates verification and control and allows senior management to operate on the basis that, "if all subordinate managers have accepted the accuracy of their figures, the consolidated figures must be correct". This ensures a high degree of reliability and confidence in the information.

As a result of the detailed analysis contained in the general ledger, it is possible to operate the financial system in such a way that very little additional processing is required at year end over that required at month end. While some difficulties were encountered at the end of the first year of operations since not all procedures were fully in place, it was still possible to table the year end figures 17 days after the end of the year and they were signed off without qualifications by the auditors approximately five weeks later.

The Cubic Business Model

The business model referred to earlier allows the databases to be viewed as a multi-dimensional "Rubic's" cube which can be rotated and viewed in a wide variety of different ways. This permits the financial and production information to be grouped and summarized by office, department and region. Production (project) information can also be viewed by project leader, technical director, marketing director, client market segment, project discipline and client thus providing a fully market focused information capability. This information can then be used to focus marketing efforts and identify different marketing and management styles required for different market sectors as well as enabling management to evaluate the performance of individuals in terms of marketing and management contribution as well as production contribution.

In conjunction with these facilities, the activity based allocation of administrative overhead contribution by technical staff permits an accurate measurement of true profitability of individual business units or sub-units at a level which permits "level playing field" comparisons of business units. This eliminates the traditional problem of professional service organizations where the business units of those involved in management and marketing are penalized since only the production contribution is measured. Through this approach, inappropriate management decisions resulting from incorrect cost allocation can be avoided.

The system also supports attribution (allocation) of income from professional fees to the business unit employing the person doing the work. This permits the profitability of business units to be measured in terms of true, salary linked, revenue contribution as well as by the traditional method of project profitability and reduces the dependence on relatively arbitrary, rates based, costing approaches.

Senior Management Work Load and Effectiveness

Senior management have had their work load on mundane analysis greatly reduced as many of the analyses previously performed using spreadsheets have been incorporated into the system and are therefore available automatically with greatly reduced effort. Time spent resolving problems of mis-allocation and addressing queries with regard to year end has also been considerably reduced.

The multiple levels of summarization in conjunction with the high level of detail of the underlying data enable management to receive very summarized reports for routine management while affording them the capability to rapidly "drill down" to progressively more detail in order to answer queries.

Strategic Advantage

The wide variety of analyses available and the ready availability of information have freed management to be more effective while devoting less time to management and administration. At the same time, management have greatly improved scope to identify opportunities to improve operational effectiveness, increase delegation and improve profitability. They are also able to identify market related factors that can have a bearing on marketing strategy, product mix and other matters. These factors all enable the firm to offer innovative and competitive services in a competitive market. This is expected to assist the firm in creating and sustaining competitive advantage over the medium- to long- term as part of it's commitment to providing relevant, appropriate and cost effective services.

CONCLUSION

The components of a management information system (MIS) and associated financial and executive information systems have been summarized based on the experience of V3 Consulting Engineers. Certain experiences during implementation have been summarized and the objectives set for the system at the outset are reviewed. It is noted that these objectives have been met.

The benefits experienced by the firm are discussed with particular reference to issues such as timeousness and reliability of information, flexibility of analysis and control. It is noted that the work loads of senior management have been reduced while more accurate and detailed information is made available more rapidly. The ability to summarize the information in a great variety of ways while providing the ability to undertake enquiries at a very high level of detail when required, is noted as a further benefit.

It is concluded that the system has met most of the objectives set for it at the outset and that it is assisting the firm in it's objective of creating and maintaining competitive advantage through the provision of focused, appropriate and cost effective consulting engineering services.

REFERENCES

Robertson J A (1990) Report on Investigation Into Professional Practice Management Information Systems for Vorster, van der Westhuizen and Partners Unpublished report, October 1990.

September 1994

Download the V3 Consulting Engineers: The Benefits of Management Information Systems to the Professional Practice -- Article in Adobe pdf format

Section 8.2

CRM Risk Control case study -- headlines

The headlines of the CRM Risk Control case study are as follows:

1. A simple software application

2. Specified in two (2) days

3. Built in ten (10) days

4. Data engineering with full time executive input and facilitation ten (10) days

5. Extremely diverse range of management information

6. Four (4) operators captured about eight (8) times more information than twelve (12) operators would have captured previously

7. Primarily a Strategic Engineered Precision Taxonomy (SEPT) and Precision Configuration benefit

8. Presentation with client – greatest recommendation

Designing and Implementing an Integrated Risk Management System that Effectively Minimizes Your Exposure

Integrated Risk Management Conference

By Dr James A Robertson PrEng and George J Paton, Director, CRM Risk Control Consultants

SYNOPSIS

The management of risk in organizations today is becoming of increasing importance as insurance premiums and liability risks increase and as the hidden costs of risk in areas such as down-time, customer dissatisfaction and other factors increase.

Effective management of risk is therefore becoming a strategic necessity. Risk management in the area of physical risk is an aspect of business that is frequently overlooked or is approached on an ad-hoc basis. This paper sets out some of the factors that should be taken into account in implementing risk management solutions and identifies the need for such solutions to be holistic in nature. In particular, it is noted that the physical and financial components of risk management should be tightly integrated and that the management of maintenance on a risk containment basis is highly desirable.

It is concluded that the effective application of information technology in the form of an integrated loss acquisition database and management information system is vital to achieving the full potential of risk management in any organization. Some of the benefits of this approach are discussed together with a case history of a successful implementation.

It is concluded that the application of these techniques can give rise to a considerable improvement in profitability and should be a vital component of most organizations business strategy. Effective risk management supported by effective information systems can play a significant role in creating and sustaining competitive advantage.

1. INTRODUCTION

The management of risk in business today is a many faceted and complex task. Traditional approaches to risk management have focused on funding and financial issues rather than managing risk at source. As with maintenance, risk management has tended to concentrate on treating the symptoms rather than the cause. Events giving rise to large losses tend to originate from apparently insignificant occurrences with regard to wear and tear, maintenance and personnel which, with time, escalate to a point of giving rise to a major incident. The use of appropriate techniques to track small losses in a manner that enables management to analyze trends in such a way that proactive action can be taken to anticipate and prevent major losses and to identify the true cause of recurrent losses is vital to effective risk management that offers bottom line benefits.

In developing and implementing a risk management solution, it is important to recognize that a prime objective of the risk management function is to create a risk awareness culture in the organization in which there is an understanding of the adverse effects that risk exposure will have on the organization. As a consequence of this awareness and understanding, deliberate measures to minimize the potential impact on the organization should be implemented. A fundamental principle of risk management is a change in emphasis from an approach of contingency planning in the event of occurrence to proactive management directed at preventing risks from materializing. Risk management is therefore primarily a management function aimed at dealing mainly with uncertainties whilst taking cognizance of the consequences of pure risk and it's impact on business activities.

In designing a risk management solution, a number of tasks must be performed:

a. The potential impact of hazards on the effective operation of the business must be considered.

b. Steps necessary to achieve predefined objectives must be defined.

c. Risk improvement programs to reduce the probability of occurrence of risks must be developed.

d. Alternative strategies for controlling the consequences of risk and their impact on the organization must be developed.

e. These strategies must be integrated into the general decision framework of the organization.

Management activities associated with this process will include risk identification, risk evaluation, risk control and risk monitoring. Risk control involves selecting and implementing the solution most appropriate to achieving the given objective while risk monitoring focuses on determining the outcomes in order to assess the validity of the decisions made. Risk management must take place at all levels in the organization.

In determining the cost of risk, in order to measure the effectiveness of a risk management programme, factors such as insurance premium costs, retention costs such as risk control expenditure, maintenance programmes, training costs, fire protection, security and administration costs must all be taken into account. An optimum risk management solution will maintain a balance between the cost of risk improvement and the level of risk financing with the objective of achieving lower levels of risk in conjunction with greatly reduced overall levels of expenditure as shown in figure 1.

In accomplishing these objectives, a means of acquiring and analyzing comprehensive and detailed loss statistics in order to determine the impact of risk management decisions and to identify problem areas requiring attention, is highly desirable. In fact, it is unlikely that the full long term benefits of a risk management program will be achieved unless the risk management program is supported by a comprehensive information system capable of recording all relevant loss information in a manner that supports comprehensive analysis and enquiry.

FIGURE 1 : DETERMINING THE COST OF RISK

2. DEFINITIONS

In discussing risk management in the context of designing and implementing a solution, the following terms are applicable (Valsamakis, Vivian, du Toit, "The Theory and Principles of Risk Management" 1992).

a. Risk management

Risk management comprises a comprehensive range of activities for dealing with risks. As a science it identifies the methods that can be adopted to handle risks and to show the interdependence between the available alternatives. As a management function, it is used to plan, direct and coordinate activities in the pure risk area.

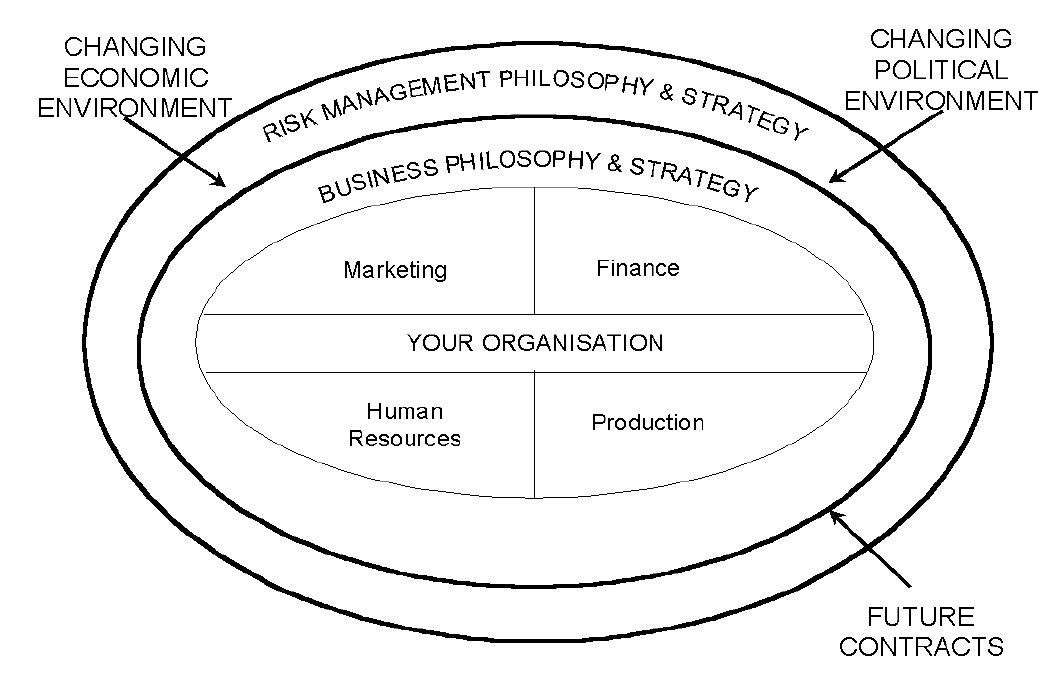

Figure 2 illustrates the relationships between business strategy, risk management and external influences.

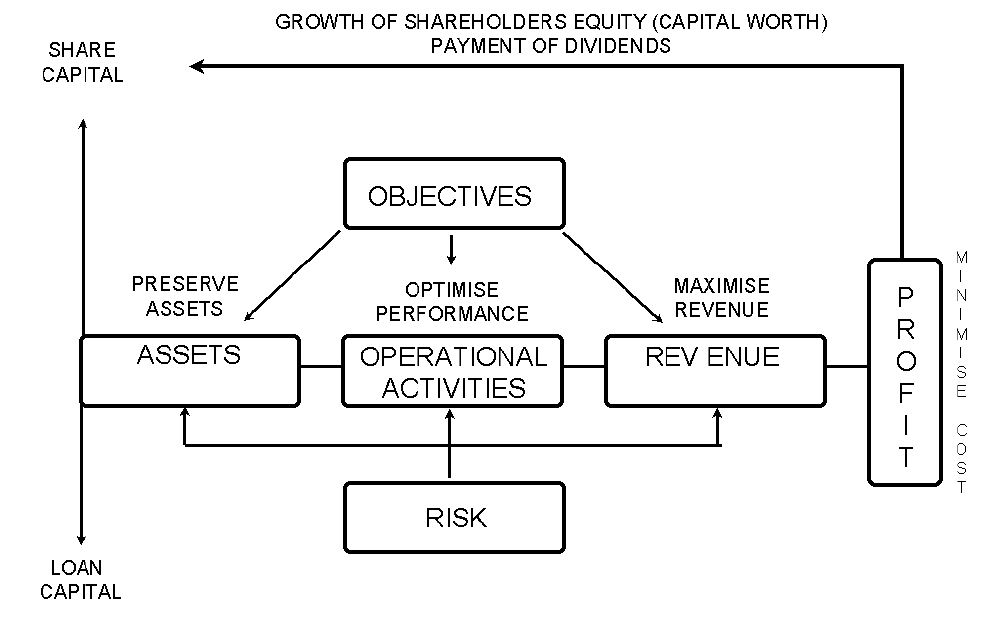

Figure 3, based on the work of the Society of Risk Managers, illustrates the areas covered by risk management and the overall objectives of an organisation.

b. Pure risk

Pure risk is a risk which results only in loss, damage, disruption, injury or death with no potential for gain, profit or other advantage.

c. Risk control

Risk control comprises the provision of appropriate levels and standards of protection for people and assets to avoid, transfer, control of or acceptance of the pure risks which have been identified and evaluated.

d. Risk financing

Risk financing involves the provision of funds for recovery from potential losses that do occur.

e. Risk evaluation

Risk evaluation is the expression of identified pure risks in an organisation in quantitative / qualitative terms in order to gauge the potential severity and frequency of occurrence of these risks.

f. Risk identification

Risk identification is the identification of the pure risks to which an organisation is or could be exposed.

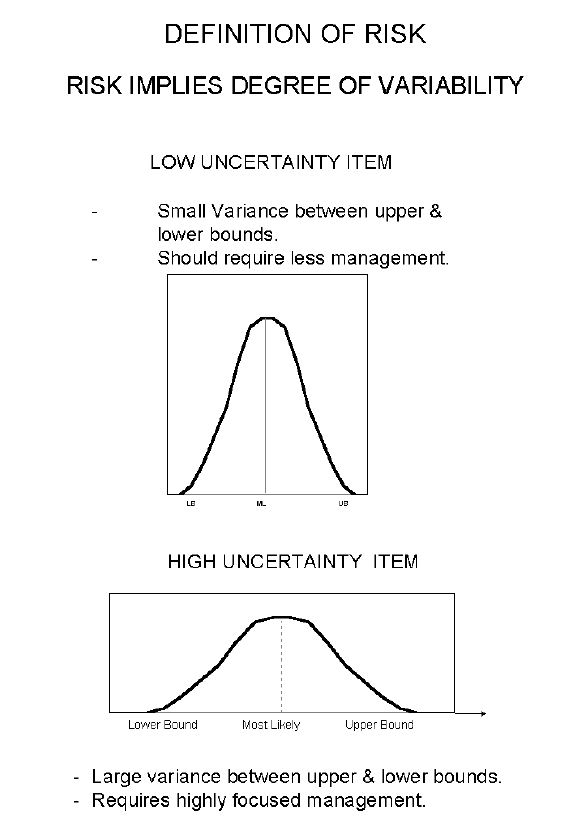

Risk can be defined as the difference between what is expected and what is experienced. In figure 4 item (a) has a greater uncertainty than item (b) and there is therefore a greater probability that the outcome of item (a) will deviate significantly from the expected value with the resultant impact on operations and severity of loss.

g. Pure risk improvement techniques

Pure risk improvement techniques are those techniques which are used to provide appropriate levels and standards of protection for people, assets and earnings. The four main techniques are as follows:

Avoidance - taking action so as not to incur the risk in the first instance.

Retention - acceptance of the risk in its current make-up or character.

Transfer - insurance, non-insurance or contractual transfer of the consequences of risk.

Control - reducing the risk by controlling its frequency and its severity.

h. Risk finance

Risk financing is intended to provide funds to assist the business to survive and recover from losses that do occur. The two main risk financing components are internal and external financing.

FIGURE 2 : THE RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN BUSINESS STRATEGY,

RISK MANAGEMENT AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES

FIGURE 3 : AREAS COVERED BY RISK MANAGEMENT AND THE

OVERALL OBJECTIVES OF AN ORGANISATION

FIGURE 4 : DEFINITION OF RISK

3. PHYSICAL FACTORS GIVING RISE TO EXCESSIVE RISK

Traditionally, the focus of risk management has been on the recording and reporting of claims as they relate to insurers. As a management tool, this did not really identify the real risk exposure of the organization. The tendency today is to focus on the overall cost of risk in an organization which is not only the insurance related cost of risk.

Physical factors that can exacerbate risk are diverse and include maintenance issues, health, environmental and other issues. A few aspects are discussed below.

The maintenance of complex plant, particularly in the production environment is often undertaken on a basis of maintaining the most visible items rather than on maintaining those items that have the greatest potential to give rise to losses or increase risk. For example, a decision to save money on the price of a valve or other low cost component can give rise to greatly increased down-time or even catastrophic failure of the plant. Most maintenance programs do not take account of these factors. An effective risk-focussed maintenance management system will focus on the loss implications of failure of a particular component and prioritize maintenance accordingly. This approach requires a different mind-set in the maintenance department and the provision of appropriate tools to enable the maintenance manager to allocate maintenance resources according to the loss implications of failure rather than traditional criteria. Sophisticated computerized information systems are required in order to accomplish this objective.

In practice, it is not uncommon for losses to result from apparently unrelated circumstances. A recent example involved a major transport operator where it was found that a disproportionate number of drivers suffered from diabetes and that their blood sugar levels were dropping in the afternoons as a result of inadequate diet to a level where serious accidents were more frequent than the industry norm. In another case, drivers were waking at 1 am in order to get to work on time and were losing concentration by mid-morning as a result of exhaustion. Many of these situations are never identified or are only identified in response to a decision from insurers to increase premiums because of poor claims history.

With appropriate information systems it is possible to monitor loss experience and identify unusual trends at an earlier stage. Under certain circumstances, it is also possible to identify relationships for more direct investigation thus reducing the time required for manual investigations.

4. INFORMATION NEEDS IN ORDER TO IDENTIFY TRENDS FOR PHYSICAL RISK CONTROL

Experience has shown that major incidents are normally preceded by a number of minor incidents over a period. Typically, such minor incidents do not attract attention and, in many cases, are not reported so that their occurrence is only highlighted during the investigation that follows the major incident. Appropriate use of a loss information recording system will enable these trends to be highlighted in terms of aggregate cost of risk, frequency of occurrence, etc. Such a system will also enable management to track the full scope of losses occurring and in some cases may highlight that the real cost of small losses exceeds the cost of the high profile losses which constitute the normal focus of attention.

Conventional loss reporting concentrates on the amount claimed from insurers rather than the hidden costs associated with the loss which includes down-time, management time, lost production, lost market opportunities, customer dissatisfaction, unremunerated overtime, staff dissatisfaction and other factors.

Compounding the above difficulties, it is frequently found in many organizations that the personnel responsible for risk control and risk improvement rarely communicate with the personnel responsible for making the financial decisions regarding insurance and self-insurance levels. In order to make strategic decisions with regard to the financial component of risk management, there is a clear need for organizations to restructure these functions resulting in a single line of responsibility for all risk related management as indicated in Figure 1. Tightly integrated risk management information is a vital component for achieving this objective.